April 19, 2016

Executive Summary

The online advertising market is saturated, and has no more room to grow. The traditional space for ads is overcrowded, and has started to shrink, as Internet users start to use ad blockers.

Ad placement companies have compensated by displaying ads on ever lower quality websites. Worse, they have led their clients into pay-per-display advertising instead of pay-per-click, much less efficient and difficult to track.

As a result, online advertising efficiency has been decreasing for years, and companies have to spend more ad dollars for the same result.

The process of ad placement has become ever more automated, obscure and complex, while intermediaries have multiplied, each taking a cut from the client’s initial ad budget.

Controls and regulations are nonexistent, and a big chunk of ad spending is being stolen, plain and simple. Customers are growing aware of the phenomenon of ad fraud. Every new fraud scandal bears the risk of customers scaling back on online ad spending. The whole ecosystem is at risk of turning from growth to decline, overnight, in a rerun of what happened in 2000-2001.

When this happens, the smaller players will be wiped out. Alphabet/Google, who has 90% of its revenue coming from online advertising, will see its business scale back to the levels of 2010-2011, while its share price will crash to the $200-$250 area. Facebook on the other hand, has a better control of who is actually seeing its ads, and will benefit from the turmoil by gaining market share.

Analysis

The online advertising market is saturated, and available ad space is in decline

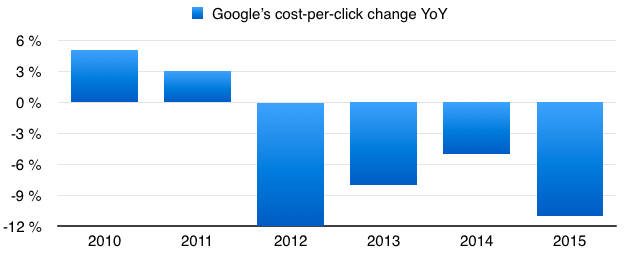

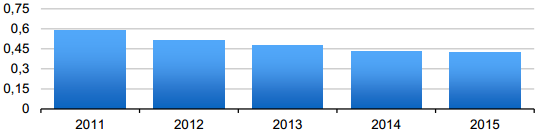

Since 2011, while Google’s revenues continued to grow, the average ad cost has declined. Larry Page described this while discussing the company’s Q4 2011 results as “a decline in ad quality” (Chart 1). More and more ads are being displayed, each one earning the company less and less.

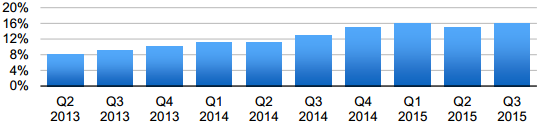

Websites have been invaded by click ads, display ads, and forced video ad views. Naturally, Internet users have grown sick and tired of this ad pollution, and have started installing ad blocking software (Chart 2).

What makes this trend worse is that users who install ad blockers first, tend to be the more sophisticated and the more affluent ones. This phenomenon has been exacerbated by Apple joining the party, and allowing third-party developers to sell ad blocking apps on its AppStore. This event has been widely covered by the media, publicizing the ad blocking movement (Chart 3).

The growth of online advertising has happened on subprime ad space, and customers have no choice but to take the industry’s word that it’s worth their money

Ad placement has become extremely automated. The growth of ad exchanges, demand-side platforms, and programmatic buying, has removed much of the need of human intervention in the process. User tracking enables advertisers to identify in real-time who is visiting any given website, and to match the visitor with an ad, instead of relying on the website’s content to draw an approximate profile of who might be viewing the webpage.

Automation has brought down the cost of deciding whether it’s worthwhile to place an ad, and user tracking has made websites’ content less relevant. It has become economical to place ads on low-end websites for cheap, because the marginal cost of placing an ad has become so low.

This means that the growth of online advertising has happened on subprime ad space. The industry’s argument is that it’s still worth their customers money, thanks to algorithms that check everything about the user, his browsing history, the cookies on his browser, his hardware data. This a compelling case, because the prime as space on the Internet (websites such as The Economist, the New York Times) are very expensive. However, customers paying for their ads to be displayed have practically no way of making sure their ads are being displayed to the right people.

Moreover, the industry has been pushing for more advertising budgets to be allocated to “display ads”, particularly on mobile, where Internet users click on ads much less than on desktops. The huge red flag with this practice is that customers have no means of knowing if their ad dollars are being spent efficiently. With pay-per-click, at least someone is coming to their website. With display ads, they are merely paying for exposure and such vague concepts as “brand awareness”.

It’s not even clear if a visitor actually sees a “display” ad, and the industry is trying to set up a “viewability” standard for this type of ads. Currently, it is assumed that an ad has had a “reasonable chance of having been viewed by the visitor, if at least 50% of its pixels were displayed on the visitor’s browser for at least one continuous second”. This definition alone lets you understand how murky this type of advertising actually is.

“Display” caught up with pay-per-click in 2015, and is projected to reach $32.2 billion in the US in 2016, vs $29.3 billion for PPC.

The efficiency of online advertising has been in decline for years

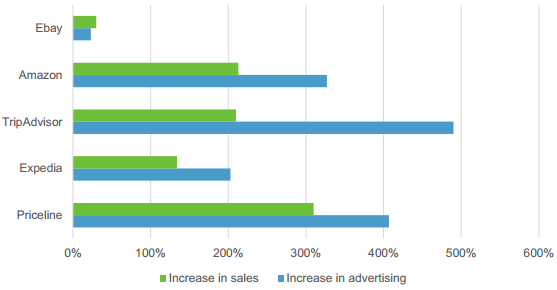

We have found five companies who provide some details about their online advertising budget: Ebay, Amazon, TripAdvisor, Expedia and Priceline. Combined, they have spent over $10 billion on online marketing in FY2015, mainly on digital ads. Their ROI of online advertising is declining: businesses need to spend more for every additional dollar of sale.

Since 2010, their online ad spending outgrew their online B2C sales. This a general trend in e-commerce: Google’s revenues are up 156% from 2010 to 2015, while online B2C sales roughly doubled. This clearly not sustainable.

The marketing departments of these online businesses are well versed in online ads, true insiders to the market, and even their advertising efficiency is declining. One can only imagine the dreadful returns for outsiders, companies like Verizon or Walmart. Very few companies are transparent in their ad spending, so it’s impossible to really know what’s going on in their marketing departments.

The decline in bang for every ad dollar spent is proof that the expansion of online advertising is being done to the detriment of customers, in ever less productive campaigns.

The ecosystem has become obscure, complex, and intermediaries are taking an ever bigger cut

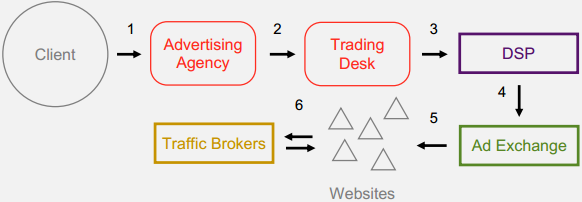

The automatization of ad placement has led to a complexification of the industry, with much more intermediaries. From a simple Client – Advertising Agency – Publisher relationship, we ended up with something like this (Figure 1):

- The Client demands the Advertising Agency to run an ad campaign.

- The Agency tells its Trading Desk what kind of ad space to buy, according to the Client’s requirements regarding its target consumer.

- The Trading Desk establishes a set of guidelines, and asks a Demand-Side Platform (DSP) to buy ad space according to these guidelines. DSPs are buying specialists, they run intelligent algorithms to pick the cheapest ad space relative to its quality.

- The DSP keeps tracking all the ad spots that come up for sale on Ad Exchanges, establishes the value of every one of them, and bids for the most relevant ones. It uses data from various data providers to come up with its valuations.

- The Ad Exchange is an open platform that enables websites to place their available ad space for anyone to buy in an auction.

- The websites themselves try to attract traffic. They receive traffic naturally, from ingoing links, search engine results, and returning visitors. However, they can also buy traffic from Traffic Brokers (for ex. Taboola and Outbrain, two « content discovery platforms »).

N.B.: we have very much simplified the way things work. Advertising Agencies can still go directly to publishers, or use Ad Networks for various degrees of customization. We are dealing there with the ad placement system that has witnessed the highest rate of growth over the last years.

Twenty years ago, the client could see his ads being displayed in the latest print edition of the New York Times, and know that his ads have been seen by the specific demographic of that particular newspaper. Today, its ads will be displayed on an alphabet soup of websites, and will be seen by a wide array of visitors.

The Rubicon Project, an ad tech company, sums this up in its 10-K filing for FY2015: “Due to the size and complexity of the advertising ecosystem and purchasing process, manual processes can no longer effectively optimize or manage digital advertising. […] This has created a need to automate the digital advertising industry and to simplify the process of buying and selling advertising.”

The customer has very little way to control and check if his advertising campaign is being done properly. He has to take the insiders’ word for it. This obviously creates a perverse incentive for insiders to place the customer’s ads on lower quality websites, and to show them to lower quality visitor profiles. Once again, the industry claims that its super-smart algorithms are making sure the customer’s money is well spent. However, something seems very wrong in this system, and here’s some insight. Look at what it costs Rocket Fuel, a DSP specialist, to buy ad space that it resells for $1 to the advertisers (Chart 7).

This just crazy. Rocket Fuel’s revenue rose from $17 million in 2010 to $409 million in 2015, while its operating margin expanded, with fierce competition in the market. Are their algorithms that smart, or are they just placing ads on lesser quality, i.e. cheaper, i.e. subprime ad space, while reassuring clients that everything’s fine?

The automation of the process, and its complexification, has gradually removed transparency. The client who pays for his ads to be displayed, is hiring more and more intermediaries. Intermediaries are raising their margins, without the client really knowing. Moreover, the client is less and less aware of who is actually seeing the ads. Unless he specifically asks to have detailed reports on who has seen his ads, the intermediaries are free to show these ads to whoever they want, wherever they want.

The websites themselves, by resorting to traffic brokers, are less aware of who their own visitors are. Content discovery platforms, such as Outbrain and Taboola, redirect traffic in new and unpredictable ways, and it’s not really clear who or how is checking the traffic’s quality. Traffic brokers’ incentive is to generate as much traffic as possible, while the websites don’t have the know-how to verify if this traffic is genuine. The big publishers themselves (Bloomberg, the Huffington Post) admit to buying traffic, although for « small percentages of their overall traffic ». As long as nobody complains, everyone has an incentive not to question the system.

There’s a great deal of fraud, controls are non-existing, and customers are growing aware of it

Technology makes it easy to buy ever cheaper ad space, with the rationalization that “we’re buying cheap stuff, but we’re making sure it’s worth the price, with artificial intelligence, machine learning and big data”. Without controls, we’re bound to end up buying worthless things while pretending that they’re valuable. Think of the subprime bubble: when everyone who could qualify for a mortgage got one, mortgage lenders started making loans to people who should never have qualified.

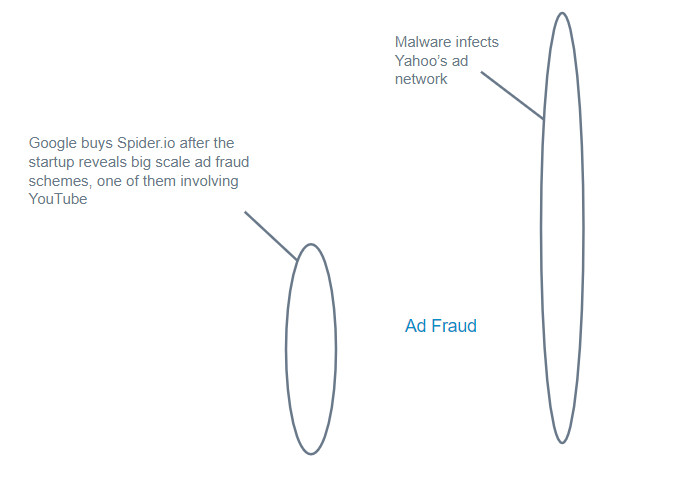

Lesser incentives to control and account for the buying of ad space are leading to fraud, and the media is starting to report on the phenomenon (Chart 8).

TechCrunch reported in January 2016 that ad fraud could reach $8.2 billion in 2016. Clients are being deceived on the quality of people who are seeing their ads.

- ads are placed on ineligible websites (porn sites, illegal video streaming, fake or stolen content, pop-ups and zero-sized images).

- ads are being clicked and seen by fake visitors. Groups of professional ad clickers (“click farms”) in countries with low labor costs (India, Pakistan, Egypt) make it look like a lot of people are engaging the ads. Bots are simulating visitors, emulating browsers populated with high-quality cookies and human-like behavior (mouse movement, page scrolling).

Independent studies have revealed that ad campaigns are polluted by fake clicks and bots. An experiment by the traffic quality verification startup Oxford BioChronometrics has shown that under certain circumstances, bot traffic generated by ads on Google, LinkedIn and Facebook may be as high as 90%. Bots can be highly evolved, emulating a human-like behavior, and virtually impossible to detect, rendering ad campaigns useless. “Traffic arbitrage”, where an intermediary buys cheap (fake) traffic and resells it to traffic brokers or publishers, is virtually risk-free to the perpetrator. At worse, his account will be shut down.

Google doesn’t mention “fraud” even once in its SEC filings, but the smaller players, such as Rocket Fuel and Millennial Media, refer to it more than 15 times on average in their 10-K, as a risk factor. Google’s operational stance is that its own customers should check the quality of the visitors its advertising platform is bringing in. Google has setup a form to claim a reimbursement for fraudulent traffic (if ever its customers were able to identify it, and prove that it was fraudulent), but makes no assurances as to how much it will actually pay back.

The industry has a huge incentive to downplay and hide the extent of ad fraud, as it’s very lucrative. There are only so many high-quality visitors on the Internet, and to really filter out low quality viewers would annihilate the market for subprime ad space.

We’ve seen this before, at the end of the DotCom bubble

We are living through the latest stages of the online advertising bubble, as available high-quality ad space is shrinking, leading to a decline ad space quality, and a decline of ad efficiency. Awareness for fraud is growing, and soon, clients will cut their online ad spending, and demand higher accountability. This will destroy the high-margin market of automated reselling worthless ad space, and will force advertisers to focus only on prime publishers, with expensive ad space.

This a re-run of the online advertising crash of the early 2000s, when the proliferation of banners and pop-ups destroyed any value these ads had (and led people to install pop-up killers, just like with ad blockers today). It took one Google to come up with contextual advertising to bring the market back to life.

Roadmap & Playbook

We estimate that the online advertising market has been artificially inflated since the end of 2013, and is much more mature than its pundits are claiming. 90% of Google’s revenues come from advertising. We expect Alphabet’s share price to go down by 75%. We get this number by revising its earnings down by 30%, stripping its 30x PE off its “growth premium” down to 15x, and factoring in the reputational damage. Other, nimbler “ad tech” players will be wiped out (Rocket Fuel, Millennial Media, Tremor Video, The Rubicon Project).

A larger number of companies will be impacted, as a growing number of third-party tech giants are involved in the advertising play (Oracle, Amazon, Salesforce), and we expect the whole tech sector to be hard hit by the unwinding of the bubble. A special case must be made of Facebook, as we believe that their platform is harder to crack, and they have a better ability to track their users, and fight ad fraud. They will be the stepping stone for investing in online advertising, once the dust settles.

Currently, January 2018 Alphabet puts with a strike of $400 are trading at around $8, for a 20x return should our scenario materialize.

| Probability | Event | Early signs |

| 60% | Awareness for fraud and the inefficiency of online ads grows past the point of no return over the next 2 years. The whole sector crashes as clients reduce spending and demand better reporting and transparency. |

|

| 30% | Google & al. manage to somehow improve reporting and accountability without hurting their market share. They manage to convince clients that there’s no reason to worry about the decline in ad quality and ROI. |

|

| 10% | The bubble goes on, as the decline in advertising ROI leads clients to spend ever more in a struggle for an elusive presence online. |

|

By:

Sarunas Barauskas, s.barauskas@kalkis-tech.com

Philippe Gondard, p.gondard@kalkis-tech.com

Q: Google is very serious about fraud prevention.

True, Google has a whole division dedicated to fraud prevention. Most of the people who worked for Spider.io, the startup that rang a warning bell about Youtube being polluted by fake views in 2013, still work there.

However, they are taking the approach “we’re fighting it, just trust us”. Their practice for reimbursing clients for fraudulent ad views is unclear. They have a webpage for such complaints, but the requests are treated one by one, while an automated system deserves to be put in place.

They are taking the approach that “every customer is responsible for what he’s buying”. Sorry, that’s a bunch of BS. They have a fiduciary duty to assist their clients. The whole subprime mortgage fiasco was based on the same argument. The whole online advertising ecosystem got overly complex and obscure.

Q: Google’s ads on its search engine are legit.

We mostly agree. The search engine is an amazing asset for the company. The CPC on google.com has risen year after year (the opposite of the overall CPC), it’s one of the highest quality ad real estate there is. However, its ad system has its flaws, too. You can research on Google’s own forums clients complaining that someone (a competitor) purposefully clicks on their ads until the daily ad budget is exhausted. Nothing prevents bots to click on your ads, on purpose or not, and you’ll be charged for nothing.

We believe that the search engine will survive any downturn, and will remain a cash cow for years to come. But it’s saturated, there is no more place to grow except by continuing to increase ad prices. The whole expansion since 2011, since CPC started declining, has been done on low quality, subprime ad real estate. This segment needs to be cleaned up. We’re only calling for a 30% decline in earnings, which would be maybe a 10%-15% decline in their revenues. The search engine ad segment doesn’t need to shrink at all, to get to that level.

Q: We were paid by Facebook.

I wish. Nobody here owns any Facebook shares, either. We’re not short Google. It’s just a research piece. The opinion that Facebook’s ecosystem is more efficient and better at picking fraud is not ours. It’s feedback from insiders, the middlemen who work at advertising agencies.

The piece on Virtual Reality is unconnected, we wrote it a couple of months ago. It’s a positive note, too, because we get the feeling that Facebook is diversifying away from the online advertising market and into video games. They’ve made this choice two years ago, when the other tech giants were working on smartphones. This was a smart move, objectively. We’ll see how it all ends.

Q: It’s all baseless speculation.

We base our research on subjects that are gaining traction in the overall news flow. We have found 94 articles about “ad fraud” over the last 5 years, only looking at influential, qualified sources (http://11wall.st/?to=2016-05-04&from;=2011-05-04&query;=%22ad+fraud%22&group;=all&nz;=0&k;=%22ad+fraud%22%3B&p;=y5). So, no, we’ve not dreamt this up, this something real that the media is talking about. This the whole point: as coverage of online advertising’s shortcomings grows, people will start to grow aware of it, and will start to question the system.

Q: Advertising is about building awareness, so display ads work just fine.

This a recurrent argument in tech companies. David Ogilvy, one of the founding fathers of advertising, would beg to disagree. The sole purpose of ads is to sell. Awareness is a vague, self-serving concept that’s peddled by social media experts because it rationalizes their own existence. It cuts the link between return and investment. It strips the people in charge of spending ad budgets from any responsibility when nothing happens. “Well, we spent a million bucks on ads, nothing happened, but the important thing is that now people know we exist”. OK then.

Q: Large advertisers, which comprise 95%+ of Google’s ad revenue, know what they’re doing.

First, there is no way to know Google’s market segmentation, which is very frustrating when you try to analyse the company. The last statistics go back to 2011, and were compiled by WordStream, an advertising agency, based on their own portfolio of clients. Since then, Google changed the way its API works, restricting access to data about third-party accounts, so there’s no way to know. Frankly, this a red flag, they are actually putting efforts into making the system more obscure.

We know that big accounts have dedicated teams inside of Google working for them. So yeah, the more money you have, the better you are served, that’s just life.

Most of companies don’t even disclose their ad budgets. We had to spend a lot of time just to find the five we used for our chart, and Ebay is not the best example either. Or maybe they’re the best, just cutting their ad spending because they realized it’s a losing battle.

There are inherent conflicts of interest in the system. For example, advertising agencies are typically paid a percentage of the ad budget. They are incentivized for the ad budget not to shrink, which might happen if they get a better bang for every dollar spend on ads.

Q: The pop-up killers didn’t cause the DotCom bubble to burst.

Of course not. However, pop-up killers were a very good indication that people had grown sick and tired of pop-ups, just like they are now with ads, which leads them to install ad blockers. Online ads’ efficiency as a marketing tool is well past its prime. It’s a macro measure of societal behavior. And it doesn’t bode well for businesses who make a living placing ads.

Q: Google is making money by selling its data about its users, and using the ad business as a façade.

No, we really don’t believe that. Google’s revenues have risen in line with the marketing costs of the five companies that disclose their online marketing spending.

Q: Google is cooking its books.

No, really they don’t. It would have made for a much better piece. Also my mom would have loved to see me on CNBC.

More Q&A;

Google makes money out of the ads displayed on its search engine, which are of a very high quality. The subprime ad space thesis doesn’t make sense.

What is disclosed is that for FY2015, 22% of revenue came from “Google Network Members websites”, which includes AdSense and AdMob.

The other 78% of revenue came from “Google websites”, and include (excerpt from Google”s 10-K SEC filing):

“clicks on advertisements by end-users related to searches on Google.com, clicks related to advertisements on other owned and operated properties including Gmail, Finance, Maps, and Google Play; and viewed YouTube engagement ads like TrueView (counted as an engagement when the user chooses not to skip the ad)”.

The search engine ads are part of that 78%, but it’s impossible to tell exactly what percentage of total revenues they represent.

It’s very frustrating not to be able to understand where Google’s revenues come from. In my opinion, they should disclose it, but they don’t.

However, we know Google has had some mishaps with fake views on Youtube. They are not immune. A crisis in the newly minted ad tech industry would lead to a loss of confidence in Google as well.

In theory, if a crisis of confidence unravels in display ads, Google would be globally immune. Their sales teams could even convince clients to switch from display to click, gaining market share.

However, we don’t think that a crisis in display ads could be contained. The loss of confidence would spread to click ads immediately. No executive would take the career risk of putting money in click ads, after just learning that display ads revealed themselves to be a waste of time and money.

Afterthoughts

We got tons of feedback and very interesting criticism on this piece. A lot of it deserves to be added to the article and discussed. A lot of comments came from people who obviously knew more about how the system works, than we do. Thank you for taking your time, really.